When I was hired as men’s tennis coach in the summer of 1966, the perception was that Stanford athletes weren’t tough enough. They were too involved in their studies, too soft to consistently battle for the top.

Stanford hadn’t won an NCAA team title in any sport since men’s golf in 1953. There was talk of de-emphasizing athletics, or dropping sports altogether. In the tennis world, USC and UCLA had a stranglehold on the national championship, winning 21 of 26 possible titles through 1971.

But I always liked a challenge.

I gave a talk at an annual alumni conference in Southern California in 1967. It was well attended. People were looking for something good to connect with athletics, so I gave it to them.

“I firmly believe we can win the nationals in men’s tennis,” I said.

I was laughed at, not just by people in the audience, but by people in my own athletic department. Are you kidding me? Are you serious? I’d hear it from people all the time, the excuses, even from coaches. There were a million alibis, which I detest. I hate alibis. They just reinforced my feelings. I was more determined than ever.

On January 15, I will retire as the John L. Hinds Director of Tennis and complete a Stanford career that has spanned 57 years.

While I was coach from 1967-2004, Stanford won 17 NCAA men’s team championships, and 10 singles and seven doubles titles. Stanford, a place that tolerated athletic mediocrity when I started, now holds the standard for excellence in college athletics. I’d like to think that I played a role in that transformation.

I came from Ventura, California, as the son of Stanford-bred parents -- my father played football for four years on the “goof” squad at Stanford under Pop Warner. During my undergraduate days In the late 1950s, two of my Stanford tennis teammates were Jack Frost and Jack Douglas, both Davis Cup players. But USC or UCLA had whole teams of players like that.

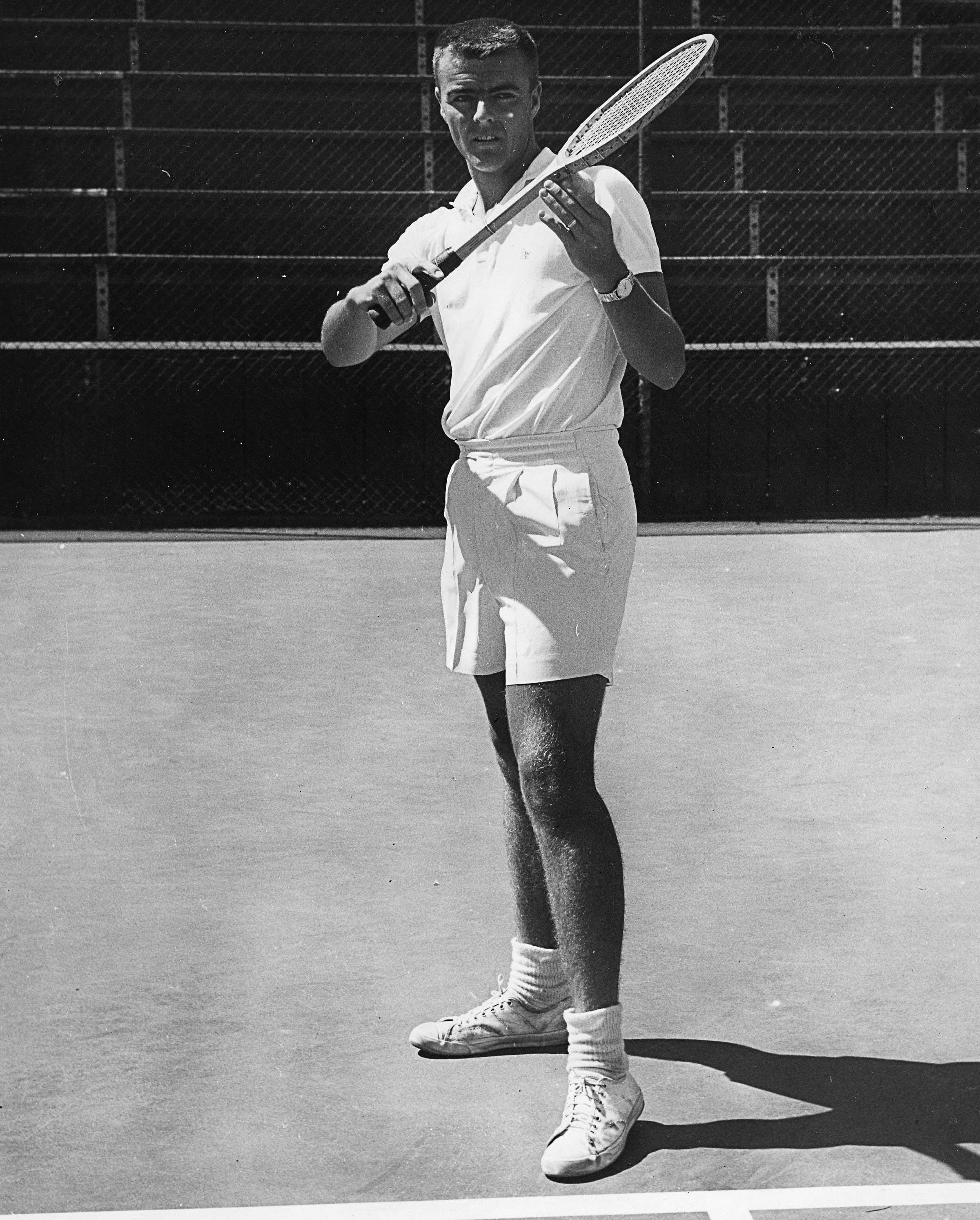

Dick Gould, during his final season as a Stanford player, in 1960

Dick Gould, during his final season as a Stanford player, in 1960

I took over from my former coach, Bob Renker, for the 1967 season. All those guys on my first team, I loved them. I still see them, we still correspond. I recently had dinner with Stanley Pasarell, who was my first full scholarship.

Like I said, I loved those guys, but my first varsity team was probably the third-best tennis team on campus, behind my freshman team (in those days freshmen could not compete on varsity) and the group of outstanding players enrolled in Stanford graduate schools. There was no pro tennis then, so there was no motivation to get serious enough to pursue tennis as a career. It was hit and giggle. Come out, take your shirt off, get some good rays, play a little tennis for a couple of hours and have a few beers. That was it.

It was a hard culture to break.

To turn the program around, I knew I had to get a great player. But everyone’s afraid of being the first. I just missed on a couple, just barely, barely missed. One guy said, I’ll go if he goes, and then the other guy goes somewhere else. I finally got one, but no one followed him up and he transferred after his freshman year.

The breakthrough came in 1969 with a guy named Roscoe Tanner. I sent him many handwritten recruiting letters that basically read, “Roscoe, you have the chance to start something new and big by coming to Stanford. If you go to one of the other top colleges in tennis, you’ll be just another player in a long line of champions, but at Stanford … “

Roscoe was admitted to Stanford, but signed a conference letter of intent with Tennessee in his home state. But during the early summer, he started to waver from his original decision.

Roscoe called me in August. “Would Stanford still honor my acceptance for admission even though I missed the deadline to accept?”

I got on my hands and knees to the admissions office, pleading, saying, ‘We’ve got to get this guy. This is our chance.’

Well, Roscoe did come and he was very popular among the players, a very charismatic guy. People loved to watch him play.

He never won a team or singles championship in his three years, but Roscoe created the foundation for Stanford’s success. He was the 1972 NCAA doubles winner with Alex “Sandy” Mayer, and a two-time singles finalist. Stanford placed second in Tanner’s final season before turning pro and won its first championship the next season, with Mayer leading the way. This started a run of six titles in nine years. Roscoe went on to win the Australian Open in 1977 and reached the 1979 Wimbledon final before losing to Bjorn Borg.

Gould stands proudly with his first NCAA championship team, in 1973

Gould stands proudly with his first NCAA championship team, in 1973

From 1973 through the end of my coaching career, all but one player who was offered a full scholarship and was admitted, came to Stanford. If we targeted an individual and they could get in, we got ‘em. To get to that point, it took work and innovation.

In those early years, I was an unknown. I didn’t play after college, I was a club pro, a high school teacher and a junior college coach. I was a nobody nationally when I took over at Stanford. I had to get to know these guys so I could recruit them. How could anyone turn down admission and a free education to this great university, especially since we were now operating at the top of the collegiate tennis world?

We got this idea of using the age-group circuit to our advantage. Every kid in the nation in the 16s and 18s age groups played in the Cal State Championships in San Jose one week and the National Hardcourt Championships in Burlingame the next to start the summer of competition. It was part of a 6-8 junior tournament circuit that determined who would be selected for major international matches overseas.

We asked the USTA to host a national training camp at Stanford. The USTA was holding camps anyway, why not save money by having the kids arrive here early to train and then play in the two local tournaments. The players would arrive 10 days before the San Jose event and the USTA would run everything. I attracted sponsorship money to pay for it, and we would give them an experience they’d never forget.

For 10 days, every top junior was here – Jimmy Connors, Eddie Dibbs, John McEnroe, Harold Solomon, Dick Stockton. No one missed this. They lived in a dorm, played like crazy and we treated them right.

We had first-run movies. They saw a James Bond film that hadn’t even been released yet. They got bussed up to The City for a nice dinner at Fisherman’s Wharf, sat in the clubhouse at a Giants game, played at local tennis clubs and were treated to barbecues afterward. We did everything first class.

I was not the coach. I was the glad hander. ‘Hey Johnny, how are you doing this morning?’ ‘Joe, how are you hittin’ ‘em?’ I got to know them. That was really how we got going.

After the San Jose and Burlingame tournaments began, I convinced the players who hadn’t participated in the USTA camp to take the commute train to Stanford. They’d walk across the street to campus and then I could show them around. Free unofficial visits. They get used to the area, see how beautiful it is, get to know the campus. How could we not succeed?

Our budget wasn’t very big then. I only made home visits to clinch the deal. However, I did write personal notes to each recruit each week. John McEnroe was already clinched, so I didn’t visit. We had three McEnroe brothers in our program – John, Mark, and Patrick – and I never went to their home. I didn’t have to.

John attended Trinity School on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Good school. Good student. Once he was admitted to Stanford, he was always going to come here.

During his senior year at Trinity, he played a few spring pro tournaments in an East Coast circuit as an amateur and did well enough to earn a wild card into the qualifying draw of Wimbledon. He won his first match, and kept winning. At 18, he became the youngest Wimbledon semifinalist in history.

He was on a hot streak, so he kept playing through the summer. He reached the fourth round of the U.S. Open. I thought I’d never see him.

When school was getting ready to start, he called me.

“Coach, I’m at the airport. Can you pick me up as soon as you can?”

I teased, “I gave your scholarship away. I thought you were turning pro.”

Silence.

Then we both cracked up on the phone.

•••

Gould adeptly handled John McEnroe in 1978

Gould adeptly handled John McEnroe in 1978

•••

He played so much that summer, I didn’t want him to touch a racket the entire fall. One of the best things I ever did. He was fresh by the end of the year.

Mac started practicing in January and had a month to prepare for our first event, the national team indoors.

What’s my lineup going to be? I’ve got Matt Mitchell, the defending NCAA singles champ. I’ve got Bill Maze, a year older than Matt and a tremendous rival going back to their age-group days. How do I not give these guys a chance at Mac just because he won at Wimbledon?

I say, “OK, guys, you’re all going to play each other.” I figure it’s going to be 1-1, 1-1, and 1-1. That seems to happen every time. Well, McEnroe won both in three sets and then Maze beat Mitchell in three. I also had Perry Wright, who was really good, and he should get a crack at No. 3. He played Mitchell and beat him. We were so deep that the NCAA singles champion was No. 4 on our team to start the year.

In that first tournament, after Mac finished, he immediately was there to console a loser or congratulate a winner as the teammate walked off the court. He was incredible. Right away, I knew what a team player I had.

John was the No. 1 player in the country. Billy lost to McEnroe in the NCAA semifinals. Matt was ranked No. 6 or 7 and Perry was No. 12. That’s how good that 1978 team was. We went 24-0, the first of three undefeated seasons in my career. The others were in 1995 and 1998, which was one of the best teams in collegiate history.

I never had a team accomplish what that 1998 team accomplished. Flat out, no way. We went 28-0 and lost only three dual-match points the entire season. We swept every match in the NCAA tournament. Four different players shared the No. 1 position and all went undefeated in that spot.

Bob Bryan won the NCAA singles title, defeating teammate Paul Goldstein (now our men’s coach) in the finals, and then he teamed with his twin Mike to win the doubles crown. It was our fourth consecutive NCAA team title and the Bryans would go on to become the greatest doubles team in history, winning 16 Grand Slam championships together and an Olympic gold medal.

As for Mac, he left after one year and became one of the game’s all-time greats. He won the first of his seven Grand Slam singles titles a year after leaving Stanford, at the 1979 U.S. Open. He won Wimbledon three times in a four-year stretch, and had a series of epic Grand Slam finals battles against Borg in 1980 and ’81.

A year after his only season at Stanford, John McEnroe won the U.S. Open

A year after his only season at Stanford, John McEnroe won the U.S. Open

What did Mac get out of his Stanford experience? He really appreciated his days as a student – he liked the school, he liked the guys. He really enjoyed the team. We’re still close today.

With charismatic guys like Tanner, our small stadium, which was built in 1926, was no longer big enough. We had a full house of 600 there to see big matches, with people lying on their bellies to look under the hedges, which were the backdrop to the fences in those days.

We also had Maples Pavilion just a few yards away. After basketball season, it was unused. Why not play indoors?

I took one of our players, Nick Saviano, to a warehouse in City of Industry near Los Angeles to see a carpet surface called Sportsface, previously used in a defunct pro indoor tournament. An alum helped pay the $10,000 to buy the 120’ x 60’ surface. We rolled out a section and it looked good, and had it shipped to Stanford.

On the third week of April, we always played USC and UCLA on Friday and Saturday nights. So, we started the indoor experiment with them. We played Nos. 3-6 singles and Nos. 2-3 doubles outside, then we went inside at 6:30 p.m. for competition on a single court that we set up over the floor at Maples. That’s where we finished the team match, first with No. 2 singles, followed by No. 1 singles, and finally with No. 1 doubles.

The band was there, the Dollies were dancing. KZSU was broadcasting. The Stanford Daily produced a special 16-page issue just for tennis. People tailgated. This was a big thing.

The first two matches drew 14,000 fans, the largest two-day crowd ever to see collegiate tennis. We outdrew the pro tournaments at the Cow Palace near San Francisco.

In 1978, the Stanford men and women played exhibition mixed matches against the Golden Gaters of World Team Tennis. More than 5,000 showed to see McEnroe play Mayer, who was then with the Gaters. McEnroe lost, and the Gaters barely won.

Other schools tried it, but it never really worked. We had as many as five indoor matches in a year. But the crowds started dropping. When you have 3,000 in a 7,000-seat arena, it looks empty. By that time, in 1989, we had built the other part of our stadium and tried to build the attendance outdoors. We never did go back inside. Now, with the hanging scoreboard at Maples, we couldn’t even if we wanted to do so.

My strategy was that every four or five years, I had to do something that showed we were energized, we were revitalized, and not just sitting on success – that we were trying to do something that had never been done before. We always wanted to project this image that Stanford tennis was never standing still or becoming complacent.

Roscoe Tanner (left) and Sandy Mayer (right) won the 1972 NCAA doubles title and helped ignite the Stanford dynasty

Roscoe Tanner (left) and Sandy Mayer (right) won the 1972 NCAA doubles title and helped ignite the Stanford dynasty

Some of our innovations included combining the men’s and the women’s programs at the outset of Title IX, in 1975, long before women’s sports were fully embraced at most schools. We celebrated our history with the placement of pillars recognizing our NCAA champions and Grand Slam winners at our stadium entrance. We designed the first electronic scoreboards for tennis and the first video board for tennis. We initiated streaming of matches in 1996 and later developed a unique broadcast system.

I always felt I would retire from coaching after 40 years or until going four years without a championship. The class of 2004 graduated without a title – the first senior class to do so since 1972 – and I left after 38 seasons. It was time.

My strength was teaching the serve-and-volley game -- to be aggressive and win the point at the net, not sitting back and waiting. To be proactive rather than reactive. But the game was changing. I had to decide whether to change with it or whether it was time to go. After 38 years of coaching incredible young men and the satisfaction and enjoyment it brings, I decided it was time to step back and retire from coaching.

I still think serve-and-volley still has a place in today’s game, but it is harder. The courts are slower and the rackets are different. The strings can impart so much more spin on the ball. You can hit it harder and know it’s going to go in with more margin. That lets players stay back, 10 feet behind the line, and bang the ball.

But if someone were to come along who was a serve-and-volleyer from the start, and had a good serve, it could work. It no longer is a big part of the game, but partly because it’s not being taught. There are kids who get to the net and they’re lost.

When I was coaching kids, most of them could volley. They just weren’t physically strong enough and tall enough to be able to cover the net. By the time they got to college they were, but by then they were used to being backcourters. They won’t change their game unless someone is forcing them to. But I still think there’s a place for it in today’s game.

I always tried to understand my players and see things from their perspective. I set team rules when I started coaching and quickly realized that nearly every time I set one, the rule wouldn’t hold up. Then, I was stuck with the consequences. I decided my rules would be: Don’t embarrass yourself, your family, your teammates, the university, or me. That gives you a lot of latitude, but you’d better own up to it. This philosophy worked fine for me.

In college, they know everything and they know nothing. You have to learn by making mistakes. A lot of times parents won’t let you make mistakes nowadays. But when you make a mistake, you need someone to support you and back you up. I tried to be that person.

They may not have liked me too much at times -- I’m sure they felt that way if they were playing No. 3 and felt they should be playing No. 1. But I really felt we had a strong bond and we’ve tried to continue those relationships. I’ve lived their lives with them in school and after school. They’re my family.

•••

Stanford celebrates its 1981 NCAA team title

Stanford celebrates its 1981 NCAA team title

•••

In the early days, our administration encouraged me to use my interest in fundraising to strengthen our programs. I’m really proud that we raised every penny of the $20 million Taube Family Center stadium through gifts of philanthropy. Not one penny was from the department or the university. I’m really proud that nearly all of the endowment that covers our men’s program was money we also directly raised from donors. That legacy means a lot to me.

The Taube complex is now one of the best in college tennis. There is fixed individual seating for 2,393, 17 courts, a clubhouse, locker rooms, players’ lounge, video center, conference rooms, championship lighting, wireless scoring systems, and a state-of-the-art plexi-pave acrylic playing surface. The kiosk outside our stadium is a touch-screen system that allows viewing of more than 200 archived videos of Stanford-related tennis history.

But I’m most proud of the championships my incredible players won and the financial state I’m leaving the program in, which includes a generous endowment commitment from Tad Taube for the head coaching position.

I’m so proud of what this university has done, and that it’s done it the right way, in every sport. It’s just incredible. It blows my mind.

When I started, it seemed impossible to even think of winning one national championship. I was influenced by football coach John Ralston, who led Stanford to its first Rose Bowl victories in more than 30 years. He thought differently. He had a great attitude, very positive. He never offered an excuse about admissions. He answered every piece of mail and every phone call immediately.

He taught me a lot. I like to think that maybe we were the two guys who helped change the way of thinking in Stanford Athletics and turned things around.

However, I worry some about where we’re going. In our efforts to consolidate and fundraise, you don’t want to discourage creativity, and I hope that’s not the case at Stanford. It’s been the beauty of working here for me – these dream positions as Tennis Coach and then Director of Tennis have truly – for over 51 years – been my hobby, not my job!

It’s been a great ride. Fulfilling in so many ways. I’m really proud of it. Humble, but very proud.

It’s been a blast.

•••

Dick and Anne Gould

Dick and Anne Gould

•••